In 2015, the Government of India set a huge renewable energy capacity target of 175 gigawatts (GW) by 2022, for transitioning to a low-carbon pathway. Of this, 40 GW was expected to be achieved through decentralized and rooftop scale solar projects. According to a report by IEEFA, the share of rooftop solar to-date is just 14 per cent of the cumulative solar installation in India.

This is well below the run-rate anticipated by the Government of India’s ambitious 2015 renewable energy plan. The increased adoption of rooftop solar in Indian states can be attributed to high-retail tariffs for C&I consumers, favourable net metering policies, corporate social responsibility programs and increased consumer awareness. Based on a report by CEEW, published in November 2019, 17 states have currently implemented net metering, whereas 19 states have implemented both net metering and gross metering.

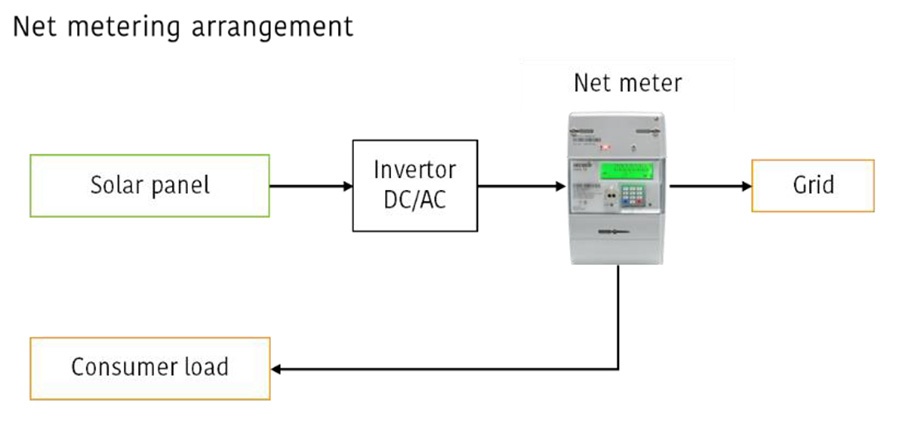

The user consumes electricity generated by the rooftop solar system and excess electricity is injected into the grid. For any additional requirement over and above the solar generation, energy can be imported from the grid. At the end of the settlement period, the consumer is only imported from the grid (Discom) the difference between solar energy generated and total energy consumed over the billing period.

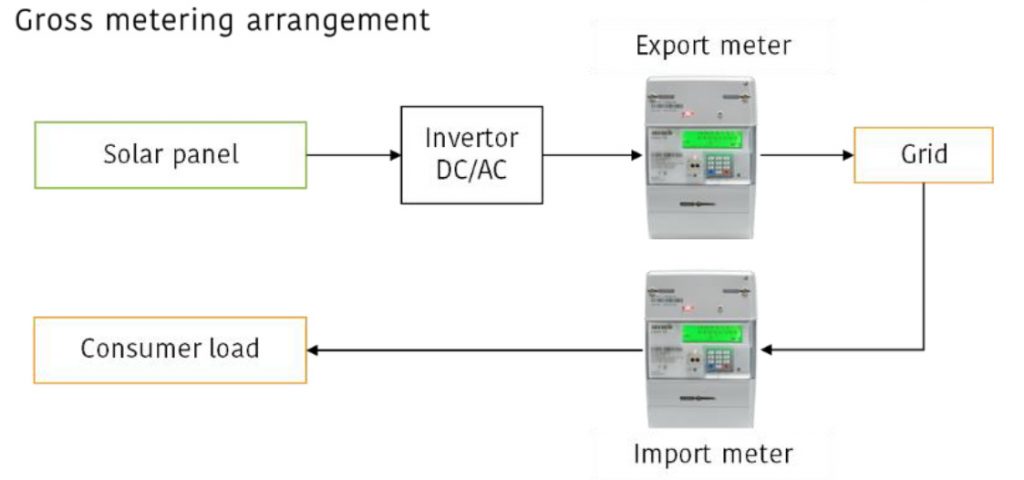

In gross metering, total electricity generated by the solar

system is injected into the grid, and consumer imports

electricity from the grid for consumption at retail tariff.

At the end of the settlement period, consumer is

compensated for the electricity exported to the grid at

Feed-in-Tariff (FiT), as determined by the state

commission.

The table illustrates financial arrangements for the same solar generation and consumption in both cases.

| Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer consumption in KWH (A) | 800 | 1000 | 1200 | 1300 |

| Solar generation in KWH (B) | 800 | 1200 | 1000 | 1050 |

| Net Energy in kWh(B-A) | 0 | 200 | 200 | 250 |

| Case 1: Net metering | ||||

| Net energy taken from discom (kWh )- C = B-A | 0 | -200 | 200 | 250 |

| Payment by Discom (INR) C*APPPC ie Rs 4/kWh) | 0 | 800 | 0 | 0 |

| Payment by the consumer (INR) – C*retail tariff ie Rs 9/kWh | 0 | 1800 | 2250 | |

| Net payable by the consumer (INR) | 3250 | |||

| Case 2: Gross metering | ||||

| Payment by Discom (INR) A*APPPC ie Rs 4/kWh) | 3200 | 4000 | 4800 | 4200 |

| Payment by the consumer (INR) – C*retail tariff ie Rs 9/kWh) | 4000 | 4200 | 6800 | 500 |

| Net payable by the consumer (INR) | 22500 | |||

Case: 1 (Net metering) – Consumer pays for the net energy consumed from the grid at a retail tariff of 9 per kWh and gets compensated at APPPC (average pool power purchase cost), which is 4 per kWh for injection into the grid (if any).

Case: 2 (Gross metering) – Consumer gets compensated at APPPC for total energy injected into, and purchases power from Discom at a much higher retail tariff.

In gross-metering, consumer needs to purchase total energy for consumption at retail tariff, which is generally higher than the feed-in-tariff (FIT); in net metering, since import of power is adjusted against export, consumer avails equivalent reduction in their electricity bill.